Do you have a favorite dinosaur? Celebrate it on May 18—International Dinosaur Day! (In fact, dinos are so big, they get two holidays: June 1 is International Dinosaur Day, too.)

Do you also have a favorite pterosaur? If you’re thinking, “What’s a pterosaur?” or “Isn’t that a dinosaur?”, read on! This is Part 1 of a two-part feature on pterosaurs, some of the weirdest, coolest creatures to ever fly. At the end of this post, you’ll find a DIY activity to make your own pterosaur!

Flocks of pterosaurs will (virtually) take to the sky this summer in Jurassic Flight 4D, the Science Mill’s new 4D virtual reality experience that lets you fly as a pterosaur through a world of dinosaurs. Join us Saturday, May 29 for Jurassic Experience, a day of dino-themed activities and the exhibit’s grand opening.

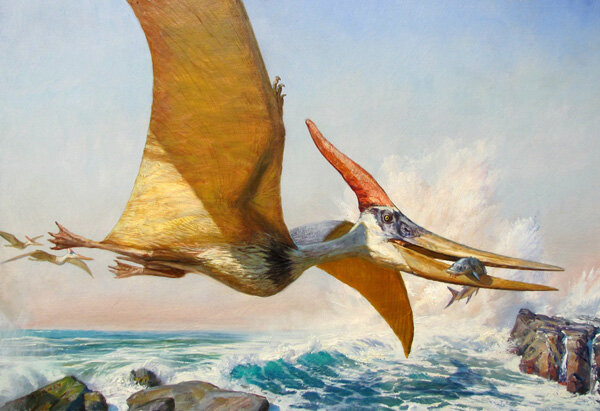

(artists: Julius Csotonyi and Alexandra Lefort, via National Park Service/ Big Bend National Park)

What’s a pterosaur?

Pterosaurs (the “p” is silent) were flying reptiles that lived 228 to 65 million years ago. They were the world’s first flying vertebrates, reaching new heights millions of years before modern birds and bats. Pterosaurs didn’t just leap or glide between heights, the way some reptiles do today. They were true fliers who could create lift by flapping their wings—what scientists call “powered flight.” (But there’s debate about how they flew; more on that in Part 2!)

“Pterosaur” isn’t one kind of animal: it’s actually a whole bunch of related species. The general name we use comes from Pterosauria, the scientific order that groups together these flying reptiles. For comparison, another order is Primates, which groups together apes, lemurs, lorises, tarsiers, monkeys and humans.

Are pterosaurs a kind of dinosaur?

Nope, pterosaurs are NOT dinosaurs. They are cousins, who share a common ancestor but evolved into distinct groups. That might seem confusing: pterosaurs lived at the same time as dinosaurs and, well, don’t they look like dinosaurs?!

Scientific classifications go more than skin deep; they’re based in a careful study of anatomy that helps scientists better understand and organize both living and extinct creatures. Part of what separates dinosaurs from pterosaurs are their hip and arm bones. All dinosaurs have a hole in their hip socket and a crest on their upper arm bone; all pterosaurs do not. This video with paleontologist Danny Barta helps explain.

What did pterosaurs look like?

Pterosaur species came in every size, “from that of a sparrow to a Cessna plane with a wingspan of 35 feet,” describes Sankar Chatterjee, a paleontologist at Texas Tech University. Kepodactylus, the pterosaur you’ll fly as in Jurassic Flight 4D, had a wingspan around 8 feet.

Pterosaurs share some very strange anatomical features. “They evolved some of the most extreme adaptations of any animal,” says paleontologist Michael B. Habib.

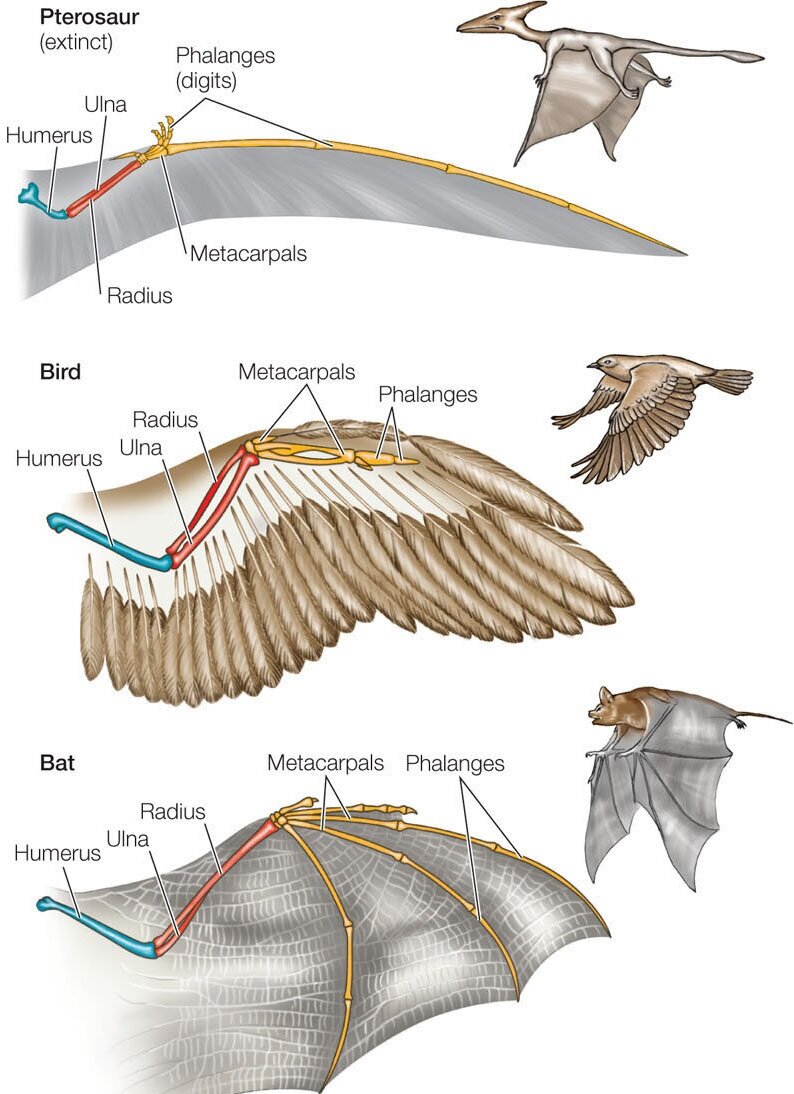

(source: MacMillan Learning)

Looooong “wing fingers”: Unlike birds or bats, pterosaur wings ran along the sides of their bodies and were held up by a super-long fourth digit—the equivalent of our ring fingers. (Pterodactylus, one of the most famous pterosaurs, is actually named for this feature: ptero = wing and dactyl = finger.)

Shape-shifting wings: Sandwiched inside their wing membranes were layers of blood vessels, muscles and actinofibrils—chord-like fibers that made the membrane rigid yet flexible. One theory is that the muscles and fibers may have allowed pterosaurs to change the shape of their wings in flight.

Feathery fur?: Pterosaurs’ bodies were covered in pycnofibers—scientists aren’t sure if this fuzz was more like fur, feathers (think: baby chick) or hair. The covering probably helped pterosaurs control their body temperature.

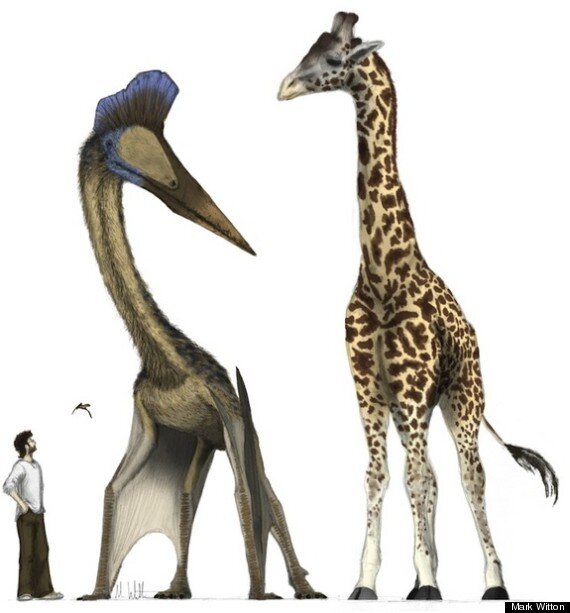

How would you measure up against Quetzalcoatlus? (artist: Mark Whitton)

Crazy crests: Many pterosaur species had crests on their heads. Some crests were fleshy, some bony and others had a membrane “sail.” Crests might have helped regulate heat or balanced out long jaws. Most likely, they served to attract a mate. Scientists think some crests were brightly colored for extra flair!

Long necks + BIG heads: Pterosaurs had oddly proportioned bodies with big heads. Some species’ skulls and necks were well over half their body length. Mega-sized Quetzalcoatlus, found in Texas, had a head and neck that made up 75% of its length, with jaws twice the length of a T.rex’s!

How did an animal the size of a giraffe, with an enormous head, manage to fly? ...Or did it? Find out in Part 2!

TRY IT AT HOME OR SCHOOL

Fold an origami pterosaur

Make a paper pterosaur that shows off some of their extreme adaptations: big heads with long jaws, crests and, of course, those amazing wings. You’ll need a square piece of paper to get started. Click the links below to download instructions.

12-step pterosaur (designed by Nick Robinson)

25-step pterosaur (designed by Fernando Gilgado Gomez)

CAREER CONNECTION:

“The cool thing about origami is that it is a very mathematical art...You can do things with pure art, you can do things with pure math, but if you put them together, you get far more satisfying results than either one alone.” - Robert Lang, physicist and origami artist

MORE TO EXPLORE

Learn how Robert Lang used artistry and computer programming to design a life-size origami Pteranodon for the Redpath Museum in Montreal!

Think like a robot inventor!

The Moxi robot’s creation is an awesome example of the Engineering Design Process at work. Engineers, inventors and other innovators follow this series of steps to design, test and improve solutions to problems.

Introducing kids to this process can help them take their ideas further and develop their planning and problem-solving skills. Since the process is a circle, it can also help kids get “unstuck” or bounce back from a flop—just find a spot to jump back in. After all, real robot inventors repeat these steps A LOT!

ACTIVITY: Be a Biomedical Engineer

VIDEO: The Engineering Design Process for Kids

CAREER CONNECTIONS:

“When I was in high school, my chemistry teacher inspired me to join the robotics club; now, as a mechanical engineer, I volunteer at my old high school's robotics club so I can inspire more kids to pursue engineering careers.”

- Alfredo Serrato, Mechanical Engineer, Diligent Robotics, Inc.